Setting the record straight: (At this point, most people are understandably confused about COVID-19 vaccines – and for good reason, many don’t trust what they read or hear. COVID-19 fatigue is rampant, and the public’s response to encouragement to get mRNA bivalent COVID-19 vaccines has been tepid.

Into this fraught environment come recent announcements from the FDA and CDC that Emergency Use Authorizations for COVID-19 vaccines have been amended to supposedly “simplify” vaccine schedules for most people. That’s perhaps questionable, but it’s also clear that the somewhat conflicting announcements will likely confuse matters even more.

However, despite COVID fatigue, it’s important that people try to understand what’s happening now, sort through the major discrepancy between the two agencies’ guidance, get some grasp of what might underlie the discrepancy, and reflect on what’s likely to come next.

Long-time FDA observer Dvorah Richman offers her expertise and analysis in this timely article. Thank you for posting it, quoting from it, and forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.)

Written by: Dvorah Richman

Most people are confused about COVID-19 vaccines, and many don’t trust what they hear. COVID-19 fatigue is rampant, and the response to mRNA bivalent COVID-19 vaccines has been tepid.

Into this fraught environment comes the Food and Drug’s April 18 announcement (and after that an announcement one from the Centers for Disease Control) that the Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech’s COVID-19 bivalent mRNA vaccines have been amended to “simplify” vaccine schedules for most people.

Putting fatigue aside, it’s worth spending a few moments to understand what’s happening now.

Important Context and Background

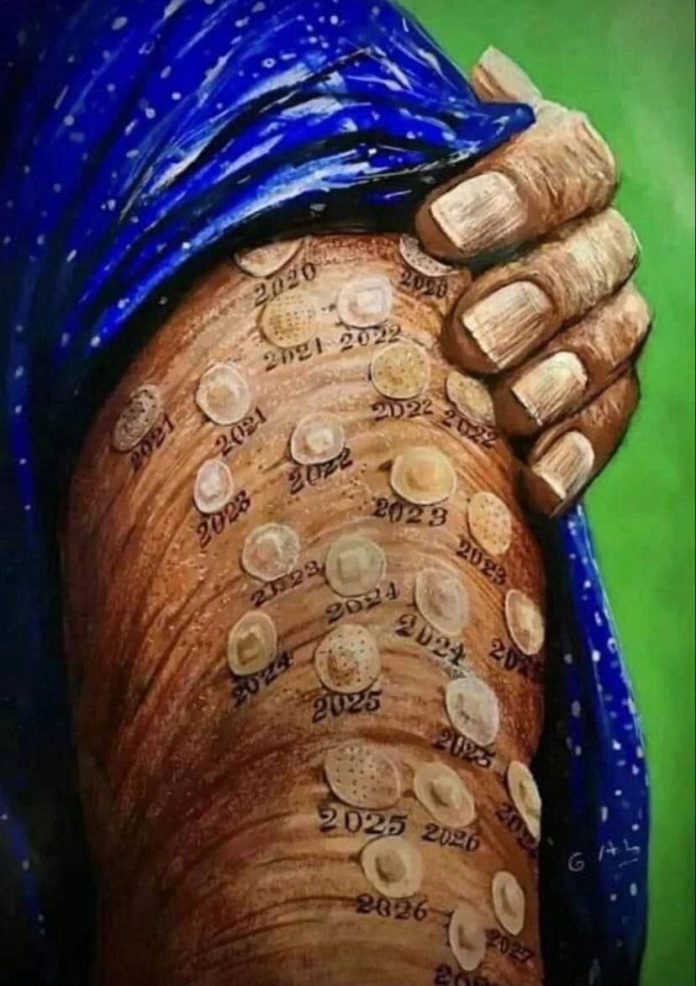

To dispel some confusion, the COVID-19 bivalent formulations discussed in the government’s April 2023 announcements are identical to the bivalent boosters offered in the fall of 2022: they target the original COVID-19 strain, as well as Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 strains.

The EUAs have been amended only to change dosing schedules, not to change vaccine composition.

While rarely explained, it’s important to know that in certain emergencies FDA can, by law, issue EUAs for use of medical products that are not approved, cleared or licensed … or to authorize unapproved uses of approved medical products.

EUAs can be issued only when there are no adequate, approved and available alternatives; when the product “may be effective”; and where the “known and potential benefits” of the product, when used to diagnose, prevent, or treat the identified disease or condition, outweigh the product’s “known and potential risks.”

EUA products do not undergo the same type of review as FDA-approved products, and FDA’s decision relies on the “totality of scientific evidence available.”

This is a lower level of evidence than that needed for FDA “approval.” Despite what you might hear or believe, EUA products are neither “investigational” nor are they deemed “safe and effective.”

Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech’s monovalent vaccines are no longer available in the United States. The companies’ bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now the mainstay of vaccine administration. Novavax and Janssen’s COVID-19 vaccines are still available in the U.S. but are used infrequently.

Government Announcements

According to the FDA: most of the U.S. population five years and older has antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (from vaccination or infection) that can “serve as a foundation” (whatever this might mean) for protection provided by bivalent vaccines. COVID-19 continues to be a “very real risk for many people,” and vaccines prevent severe illness, hospitalization and death.

Reflecting research and post-market data (summarized in FDA’s announcement), healthy people between the ages of 6 and 64 who have already received a bivalent vaccine don’t need another one. Those in this age group who have never received a Covid-19 vaccine, or have only gotten the older, monovalent version, “may” get a bivalent vaccine.

Unvaccinated children six months through five years old “may” get bivalent doses, considering their vaccine and vaccine history.

FDA also relies on research and data to support its conclusion that people 65 and older “may” get a second bivalent dose at least four months after their initial bivalent dose; and that individuals (five and older) “with certain kinds of immunocompromise” who have received one bivalent COVID-19 vaccine “may” get another one at least two months later, and “may” get additional bivalent doses at their health provider’s discretion.

Vaccine eligibility for immunocompromised children six months to four years depends on the vaccine previously received.

Despite concluding that COVID-19 poses a “very real risk for many people,” and that vaccines prevent the most serious consequences of COVID-19, FDA simply encourages individuals “to consider staying current with vaccination …” and studiously avoids suggesting that people “should” get vaccinated.

According to the CDC: On the other hand, while the CDC’s announcement generally tracks FDA’s, the CDC “recommends that everyone six years and older receive an updated (bivalent) mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, regardless of whether they previously completed their (monovalent) primary series.”

Questions Abound

Unfortunately, there is no explanation for FDA’s reluctance to push vaccines, or for the CDC’s relative bullishness.

FDA’s reluctance may reflect conflicting data, immensely complicated issues and ongoing disagreement among experts. This includes questions about how long vaccines protect against severe illness and death, and reports of adverse events (including myocarditis risk to young men).