[ad_1]

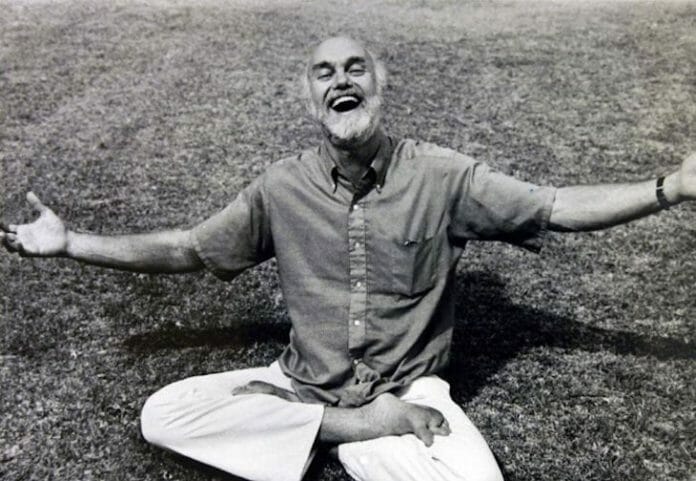

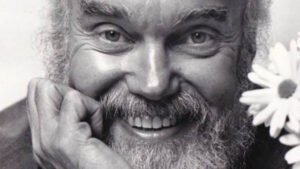

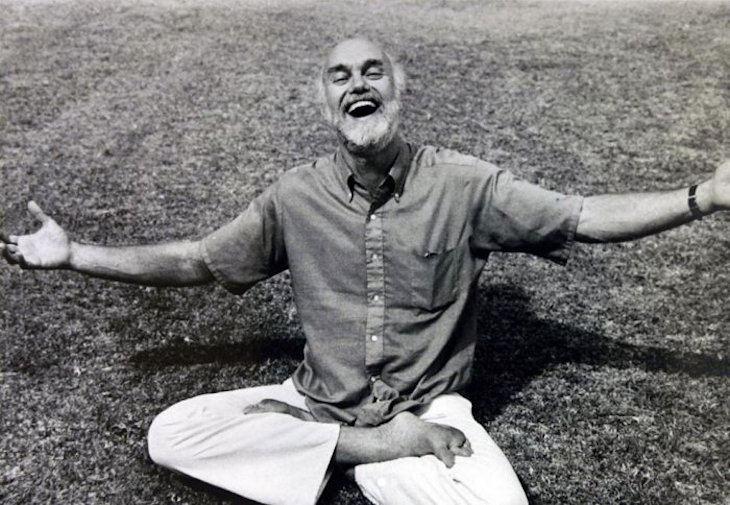

Ram Dass never called himself a guru, but he was the spiritual guide and role model for a generation of seekers. Similarly, he didn’t refer to himself as a Jew, but the way he lived his life was, in some ways, quintessentially Jewish.

I knew Ram Dass personally. The ashram in Cohasset, Massachusetts, where I lived as a monastic member for 15 years, was close to the estate of Ram Dass’s father, George Alpert. Ram Dass occasionally came to our ashram on Saturday nights for kirtan, a community songfest. When I wrote my first book, a biography of Swami Paramananda, in 1984, Ram Dass read it and wrote an appreciative review of it in the New Age Journal. Several years after I became an observant Jew and moved to the Old City of Jerusalem, Ram Dass came to my house for a Shabbat dinner.

The Alpert family into which he was born was strongly Jewishly affiliated like many Conservative Jews of that age. Like my own upbringing in Conservative Judaism, it did not feed him spiritually at all. A circa 1990 cassette tape of a panel discussion of Ram Dass with two other Jewish-born New Age spiritual leaders, including famous Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfeld, discussing their Jewish background, is a series of jokes and complaints about Hebrew School and their vacuous Bar Mitzvahs. Listening to it in my home in Jerusalem, where, at the age of 37, I had discovered the depth and spiritual power of Judaism, I felt sorry for them. An adult whose knowledge of nutrition had not deepened since he was 12 years old would be embarrassed, but how many Jews are satisfied to know nothing more of Judaism than what they learned as children?

My belief is that I wasn’t born into Judaism by accident, and so I needed to find ways to honor that.”

At the age of 60, Ram Dass confronted this lack. “My belief is that I wasn’t born into Judaism by accident, and so I needed to find ways to honor that,” he said in a 1992 interview. “From a Hindu perspective, you are born as what you need to deal with, and if you just try and push it away, whatever it is, it’s got you.” [1

Ram Dass immersed himself in Jewish sources and contemporary expositions for a lecture on Jewish spirituality that he was invited to deliver in Los Angeles. “I started to get into what it would feel like to be a very religious Orthodox Jew,” he admitted. “I began to see the heartfelt beauty of being a person who truly loves God in a Jewish way, how it relates to lineage and community, how the mitzvot are all techniques for remembering God, how halacha is a support system.” 2

Ram Dass even came to Israel at the invitation of Rabbi David Zeller. He met with a Kabbalist in the Old City of Jerusalem, a Hasidic rebbe in Tsfat, and numerous Jews who were ardently following the path of Torah, many of whom had once been Ram Dass’s students back in America.

Yet, despite his newfound appreciation for the religion into which he was born, Ram Dass never traded in his prayer beads for tefillin. He continued on the spiritual path that he had forged for himself since his first visit to India in 1967. That path, in some ways, was a very Jewish version of Hinduism. 3

Renunciation of the world or involvement with the world?

Hinduism is a religion of transcending the world. Its goal is moksha, liberation from the wheel of birth and death. The path to such liberation is meditation, through which the adept achieves a state of transcendent consciousness known as samadhi. The lifestyle conducive to success in meditation is the life of renunciation.

Holy persons in India are called sannyasins. They have renounced the world, specifically sex, family relationships, and material possessions. While Hinduism has many sacred texts, including the Vedas and the Upanishads, its concise “bible” is the Bhagavad Gita, in which Krishna teaches his disciple Arjuna about the ills of “attachment” and the ultimate value of “detachment.”

Judaism, by contrast, is the religion of sanctifying and elevating the physical world. With a few notable exceptions, the commandments of the Torah involve using one’s physical body to engage and thereby uplift physical objects by using them in the service of God: affixing a mezuzah on the doorpost, blowing a ram’s horn on Rosh Hashana, shaking a citron and green branches on Sukkot, etc. Far from the ideal of detachment, the Torah enjoins “devykut” (bonding or clinging) to God and love and involvement with other human beings. Feed and clothe the poor, lend money to the needy, love your neighbor as yourself.

Nowhere is this contrast between Hinduism and Judaism more pronounced than in their respective views of sexuality. Hinduism regards the highest path to God to be celibacy. Ram Dass’s guru Neem Karoli Baba and all the genuine gurus of Hindu tradition have been celibate. This is because of the ideal of renunciation explained above and because the Kundalini energy, which goes up the spine and culminates in samadhi in the highest chakra at the crown of the head, must not be dissipated in sexuality in a lower chakra.

On the other hand, Judaism considers the highest path to God to be marriage. With a tiny handful of exceptions, all of the sages of Jewish tradition have been married. Sexual union between husband and wife, sanctified by following the mitzvot of “family purity,” is the “holy of holies” of the Jewish spiritual path.

Deccan Herald

Deccan Herald

These opposite approaches to involvement in this world may pose a conflict for Jews following a Hindu path. Toward the end of my 15 years living in a Hindu ashram, this conflict came to a head. In 1982, a devastating blizzard struck the coast of Massachusetts, where our ashram was located. Tidal waves rising to 45 feet demolished scores of homes in the neighboring town of Scituate, and hundreds of local residents who had no place to go, including many elderly people, were put up on army cots in the local high school. The radio issued constant calls for people to take these traumatized disaster victims into their homes.

Since the ashram’s retreat cottages were then empty, I was eager to offer them for the rescue effort. While our guru, Srimata Gayatri Devi, was at our California ashram, I was the administrative head of the East Coast ashram. I telephoned our guru for her approval. She refused. She insisted that housing strangers of questionable spiritual vibrations would damage the rarified atmosphere of the ashram. I hung up the phone and wept.

Ram Dass was devoted to his guru Neem Karoli Baba, but he forged his own unique path, which actually gave free rein to the Jewish activist in him. In the 1970s, after returning to America, he founded the Hanuman Foundation, a nonprofit educational and service organization. It wasn’t enough for him to have discovered the benefits of meditation. Ram Dass developed the Prison-Ashram Project to teach meditation to incarcerated prisoners. After that, he co-founded the Seva Foundation to treat the blind in India and Nepal. He also dedicated himself to teaching workshops on conscious aging and dying. And, like his philanthropist father, Ram Dass donated the considerable proceeds of his books and lectures to charity.

Going Home

Two years before his death at the age of 88, Ram Dass became the subject of a short documentary (now on Netflix) showing his life after the stroke that paralyzed his right side.

“Going Home” shows Ram Dass in his home in Maui, where he spent his final years. His living quarters are festooned with pictures of his guru, plus a shrine with pictures of various gurus and Hindu deities. Jews, unlike non-Jews, are forbidden by the Torah to worship God through intermediaries. In this way, Ram Dass’s path was decidedly un-Jewish.

Yet, I’d like to suggest that his devotion to his guru saved Ram Dass from the egotism that ruined so many New Age teachers. As he recounts in the film, the major turning point in his life from a power-driven Harvard academic to a person cognizant of his soul came through drugs. His first mushroom trip revealed to him his soul essence. This led to Dick Alpert (as he was then known) working closely with Timothy Leary, also at Harvard, experimenting on the psychedelic effects of LSD.

Eventually, both of them were dismissed from Harvard. Timothy Leary was a disciple of my guru, Srimata Gayatri Devi, called Mataji. Tim distributed LSD to the monastic members of the ashram, who became enamored with psychedelic experiences. Mataji finally put her foot down and forbade her disciples from taking psychedelics. She told Tim, “A servant cannot serve two masters.”

Tim replied, “I disagree with you,” and broke off all connection to his guru. In 1963, he established a psychedelic commune in Millbrook, NY, and took most of Mataji’s ashram community with him. Listening to no one but the dictates of his own ego, he married five times, spent time in prison, and became a controversial, even zany, counter-culture figure.

Throughout the ups and downs that spiritual striving always entails, he remained true to the ideal of service.

Dick Alpert followed a different path. In 1967, he met Neem Karoli Baba in India, became convinced of his genuine spiritual greatness, and accepted him as his guru. Obeying a guru requires humility, and Dick chose to adopt that highest of all spiritual qualities. Neem Karoli Baba gave Dick the name Ram Dass, meaning servant of God. Throughout the ups and downs that spiritual striving always entails, he remained true to the ideal of service. His first blockbuster book, Be Here Now, defined the guiding motto of his life: “Love everyone, serve everyone, remember God.” Although tens of thousands of New Age seekers considered Ram Dass their teacher, he never assumed the role of guru.

His humility was most starkly revealed in his 1976 article in the Yoga Journal called “Egg on My Beard.” In it, he confessed how, after the death of Neem Karoli Baba, he had become involved for 15 months with Joya, a married woman with psychic powers in Brooklyn, and how he had led many of his own followers to become devoted to her. I myself heard him extoll Joya (without using her name) in a mass teaching on the Harvard campus in 1975. In the end, she proved to be a manipulative, ego-tripping materialist. Ram Dass publicly admitted his mistake. “I was totally seduced by the melodrama, like an open-mouthed tourist watching a fakir do the Indian rope trick…Finally, I had to admit that I had conned myself.” It was a public humiliation that could be acknowledged only by a person with genuine humility.

Ram Dass ended his mea culpa with: “I hope you may learn something from my example and save yourself a big detour. If your longing for God is pure, this is your strength.”

I think we Jews would agree.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130719153916/https://articles.sun-sentinel.com/1992-03-27/features/9201300673_1_torah-jewish-law-judaism

- Ibid.

- Although Westerners often conflate Hinduism with Buddhism, the two religions are very different. Buddhism is a non-theistic religion. Hinduism, on the other hand, is a religion centered on God. Ram Dass had many Buddhist friends and often taught with Buddhist teachers, but his path was Hindu. He was a devotee of God.

The post Ram Dass: The Jew in the Guru appeared first on aish.com.

[ad_2]

Aish.com is an online Jewish Newspaper. Aish is a news partners of Wyoming News.