[ad_1]

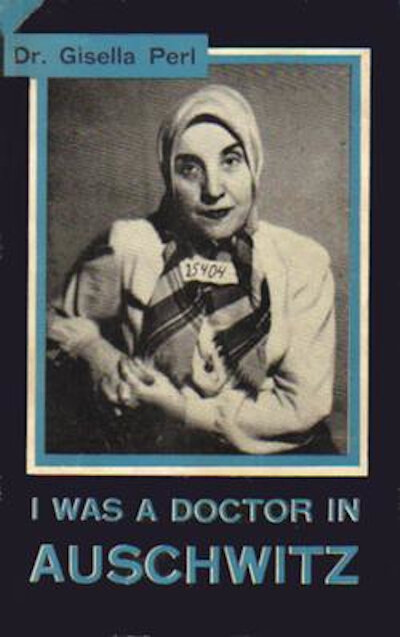

In May 1944, the Jewish ghetto in the Hungarian town of Sziget was being liquidated with all the surviving Jews being sent to Auschwitz. One of the thousands of terrified Jews forced into an overcrowded cattle car bound for Auschwitz was Dr. Gisella Perl, a distinguished intellectual who’d grown up there. After studying medicine in Germany, Gisella became one of Europe’s early female doctors, specializing in gynecology, delivering babies and offering medical care to women in Sziget and the surrounding areas.

In Auschwitz, all female doctors in the group were ordered to identify themselves. Gisella recognized the Nazi doctor giving the order. She and her husband had once hosted Dr. Victor Kapezius in their home for dinner in 1943, not realizing he was a member of the SS. Kapezius looked at Gisella with a cold smile before telling her, “You are going to be the camp gynecologist. Don’t worry about instruments… you won’t have any.Your medical kit belongs to me now.”

With that, Gisella was separated from her beloved husband Ephraim and entered the rings of Hell.

Hospital in Auschwitz

Along with four other doctors and four nurses, Gisella was charged with creating a hospital in Auschwitz’s Group C, which was designated for female slave laborers.Gisella had only one knife with which to operate; she had to sharpen it on a stone. Their hospital had no medicine and only the occasional paper bandage. The Nazis insist that it be kept meticulously clean. Each day, Gisella and her colleagues would sweep the floor with their hands. Any evidence of dirt or disarray would result in a beating or death.

Though she was trained as a gynecologist, Gisella found herself busy from dawn till night setting the broken bones of prisoners who’d been beaten by guards, operating on deep lacerations made by Nazi whips which had become infected, and treating prisoners who were sick with typhus, pneumonia, and other diseases.

Gisella was assigned to look after a contingent of 32,000 women who were kept alive for slave labor in Auschwitz.

“Those first weeks at Auschwitz were made unbearably miserable by the various skin eruptions caused by the weather, exposure, deficient food, and lack of water for drinking and washing,” Gisella wrote. “The lice plague made these eruptions more serious. We scratched in our sleep even if we were strong enough to refrain from it while awake and the sores became infected until our whole body was covered with deep, crater-like wounds.”

Gisella was assigned to look after a contingent of 32,000 women who were kept alive for slave labor in Auschwitz. Six months later she witnessed the horrific “liquidation” of this group, to make way for a batch of new slave laborers. The months that these women were kept alive were filled with unbearable misery.

Gisella wrote of one Tisha B’Av in Auschwitz, the Jewish day of mourning, when she and the other prisoners were “ordered to sit in the ashes, which, we were repeatedly told, were the last remnants of our parents, husbands, children. They were going to give us a concert.” (Like much else in Auschwitz, this concert was designed to demoralize the prisoners. Mourning on Tisha B’Av includes refraining from listening to live music.)

“From then on until late at night they (the Auschwitz prisoners orchestra) played gaudy songs…while the four crematories turned living flesh into gray ashes. Ten thousand persons were burned in each of the furnaces that day. The unceasingly dancing flames were brighter and hotter than the sun; heavy smoke filled our nostrils, and thick, black soot settled over the motionless multitude while the expressionless faces of the thirty-two thousand defeated women, whose sorrow was far beyond the comfort of tears, registered nothing but blank despair.”

Gisella Perl

Gisella Perl

Surrounded by death, Gisella frequently saw women and young children being brutally murdered, often thrown alive into the raging crematoria. She was determined to give her fellow prisoners a way to feel human again, even if only for a few moments. She began a ritual that soon spread throughout the barracks of Auschwitz. Each night in the barracks, locked in the pitch dark, she would whisper to the women nearest her, fantasizing about the perfect day. Together they would describe how they “went shopping”, “visited a museum”, or “enjoyed a delicious meal” that day. For a few moments, they remembered what life outside of Auschwitz could be.

Pregnant Women in Auschwitz

As the Jewish communities of Hungary were sent to Auschwitz during the Spring and Summer of 1944, women who were pregnant were ordered to make themselves known to the authorities. They were taken to a different camp where, the Nazis told them, they would receive double bread rations. “Group after group of pregnant women left Camp C,” Gisella wrote. “Even I was naive enough, at that time, to believe the Germans, until one day I happened to have an errand near the crematories and saw with my own eyes what was done to these women… They were beaten with clubs and whips, torn by dogs, dragged around by the hair and kicked in the stomach with heavy German boots. Then, when they had collapsed, they were thrown into the crematory – alive.”

Knowing the brutal fate that awaited pregnant Jews there, she would do all she could to make sure no prisoner was pregnant in Auschwitz.

Gisella could scarcely believe what she’d seen. She ran back to the barracks and urgently told her fellow prisoners the horror she’d witnessed. “Never again was anyone to betray their condition,” she urged them. Gisella made a solemn vow to herself: knowing the brutal fate that awaited pregnant Jews there, she would do all she could to make sure no prisoner was pregnant in Auschwitz.

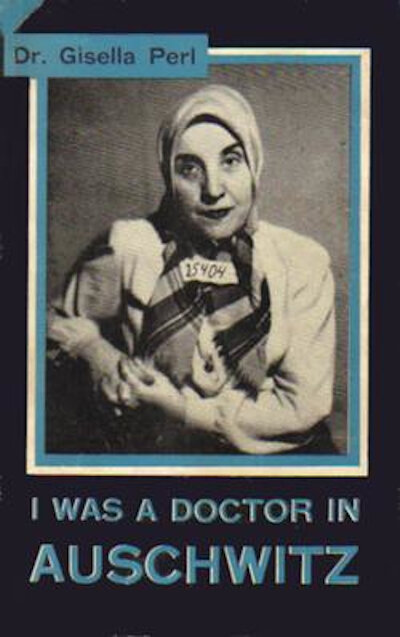

Abortion in Judaism is mandated when it will save the life of an expectant mother. “It was up to me to save the life of the mothers, if there was no other way, than by destroying the life of their unborn children,” Gisella recalled in her memoir I Was A Doctor in Auschwitz, published in 1948. With no disinfectant or water – and in absolute secret – Gisella performed abortions on pregnant prisoners, allowing them to live for at least a little more.

Risking Her Life to Help Others

Being a doctor allowed Gisella to help prisoners in small ways.When Nazis demanded blood samples from hospital patients to see if they harbored infectious diseases, knowing that patients with typhus and other illnesses would be killed, Gisella and her fellow doctors sent samples of their own blood instead. When the SS came to send the sickest patients to the crematoria, Gisella could sometimes smuggle patients out of the building, sending them back to their barracks.

“Without Dr. Perl’s medical knowledge and willingness to risk her life by helping us, it would be impossible to know what would have happened to me and other female prisoners… She was the doctor of the Jews,” explained one survivor, identified only as “Ms. B”, in testimony at the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. Many inmates called her “Gisi Doctor,” an endearment that reflected their deep love and admiration.

Gisella was forced to work closely with Dr. Josef Mengele, the notorious Auschwitz physician who performed experiments and vivisections on prisoners.

Gisella was forced to work closely with Dr. Josef Mengele, the notorious Auschwitz physician who performed experiments and vivisections on prisoners. His demands were capricious. In one particularly cruel ploy, Dr. Mengele told Gisella that from now on, Jewish women were allowed to have children in Auschwitz. “The children, of course, had to be taken to the crematory by me, personally,” Gisella later wrote, “but the women would be allowed to live. I was jubilant. Women, who delivered in our so-called hospital, in its clean floor, with the help of a few primitive instruments that had been given me to, had a better chance to come out of this death camp not only alive but in a condition to have other children – later.”

There were 292 pregnant women in Gisella’s hospital some time later when Dr. Mengele returned, brandishing a whip and a gun. He had all the patients loaded onto a single truck and driven to the crematoria, where they were thrown alive into the flames.

Delivering a Baby in Bergen Belsen

After serving seven months in Auschwitz, Gisella was transferred to a Nazi labor camp near Hamburg to serve in the hospital there. At the beginning of March 1945, she was transferred to Bergen Belsen. “Bergen Belsen can never be described,” she wrote, “because every language lacks the suitable words to depict its horrors… There were no crematories to burn the bodies. They were left where they had died until someone who had enough strength left to move dragged them out and threw them on the dung heap. Everybody had typhus, everybody was covered with lice, eaten alive by rats, and there was no food, no water, no medicine. The narrow streets between the blocks were full of skeleton-like men and women who crept around in the dirt, searching for a drop of water, a bite of food, until, utterly exhausted, they sat down beside one of the mountains of corpses to die… I arrived there on March 7, 1945, and the next day I found the bodies of my brother and my twenty-year old sister-in-law among the dead….”

Gisella in happier times

Gisella in happier times

Gisella was put in charge of the “hospital” in Block III, where she tried to comfort the dying.On April 15, 1945, a new patient was brought to the hospital – a young non-Jewish member of the Polish resistance named Marusa. She was pregnant and in labor. As Gisella sat with her, delivering her baby, she heard commotion outside: British troops were liberating Bergen Belsen. After the birth, Marusa began to hemorrhage dangerously. With no medicine, instruments, or even running water, Gisella ran outside and begged the newly arrived British troops for help. Finally, she asked a tall officer if he spoke French. When he said yes, she took him to the hospital. The officer was Brigadier General Glyn Hughes, the first Allied physician to enter Bergen Belsen. Within half an hour he’d supplied key medical items and Gisella was able to save the young mother’s life.

Testifying to Nazi Atrocities

After the Holocaust,Gisella wandered through Germany on foot for 19 days, looking for her family. She learned that her husband and son had been murdered. Her husband Ephraim had been beaten to death by Nazi guards just days before liberation. The whereabouts of her daughter, Gabriella, remained unknown for years. It seems that Gisella entrusted her daughter to the care of a non-Jewish couple during the war, then lost touch with them. When she wrote her memoirs shortly after liberation, Gisella didn’t even mention her daughter: perhaps it was too painful to wonder what had become of her child or perhaps she felt guilty about not having been able to find her.

After the Holocaust, Gisella was resolute: she had to tell the world what occurred. She wrote a heart-rending plea to the US Department of Justice: “I read in the papers of the capture of Dr. Mengele, chief physician at the Oswiecim (Auschwitz) Death Camp. I want to offer my services as material witness against this most perverse mass murderer of the 20th Century… I was a prisoner in Auschwitz, forced to act as medical doctor under his command. In this capacity, I had every opportunity to observe Dr. Mengele at his most bestial. I can testify from personal observation that he was responsible for all the atrocities and that he invented most of the perverse forms in which they were committed.”

Instead of facing justice, Mengele was helped to escape Germany by the Red Cross. He lived openly in Buenos Aires until his death in 1979 in a swimming pool accident.

Gisella lectured tirelessly about her experiences and penned her memoir. She called herself an “Ambassador of the Six Million.” An encounter with Eleanor Roosevelt in 1948 changed the trajectory of Gisella’s life. Mrs. Roosevelt had heard something of Gisella’s story and invited her to lunch. Gisella explained that since she kept kosher she couldn’t possibly go to lunch in a restaurant with the First Lady: Mrs. Roosevelt replied that in that case, she would host a kosher lunch. At the meal, Mrs. Roosevelt urged Gisella to return to her practice of medicine, which she had always loved, and to pursue her career once more.

Each time she attended a delivery, she paused to utter a prayer: “God, you owe me a life, a living baby.”

Gisella took this advice and accepted a job in the labor department of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York where she was the only female physician. Later, she opened her own practice dedicated to helping women overcome infertility. Many of her patients were Holocaust survivors she had known in Europe.“I was the poorest doctor on Park Avenue, but I had the greatest practice: all of Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen (survivors) were my patients,” she told the New York Times in 1982.

In 1978, while Gisella was lecturing about her experiences, she encountered someone in the audience who told her that her daughter Gabriella was alive and well and had built a new life for herself in Israel.

Gisella moved to Israel to be with her. She worked as a volunteer in obstetrics clinics run by Jerusalem’s Shaare Tzedek Hospital. Each time she attended a delivery, she paused to utter a prayer: “God, you owe me a life, a living baby.”

The post The Abortionist of Auschwitz appeared first on aish.com.

[ad_2]

Aish.com is an online Jewish Newspaper. Aish is a news partners of Wyoming News.